Conflicts are inevitable in IT and product teams. They're due to expectations, overloaded processes, unclear agreements, and human emotions.

A conflict is a signal of a problem in the system of work or communication, not someone's «badness».

The manager's job is not to find the culprit, but to restore working interaction, preserve the result, and prevent a repeat.

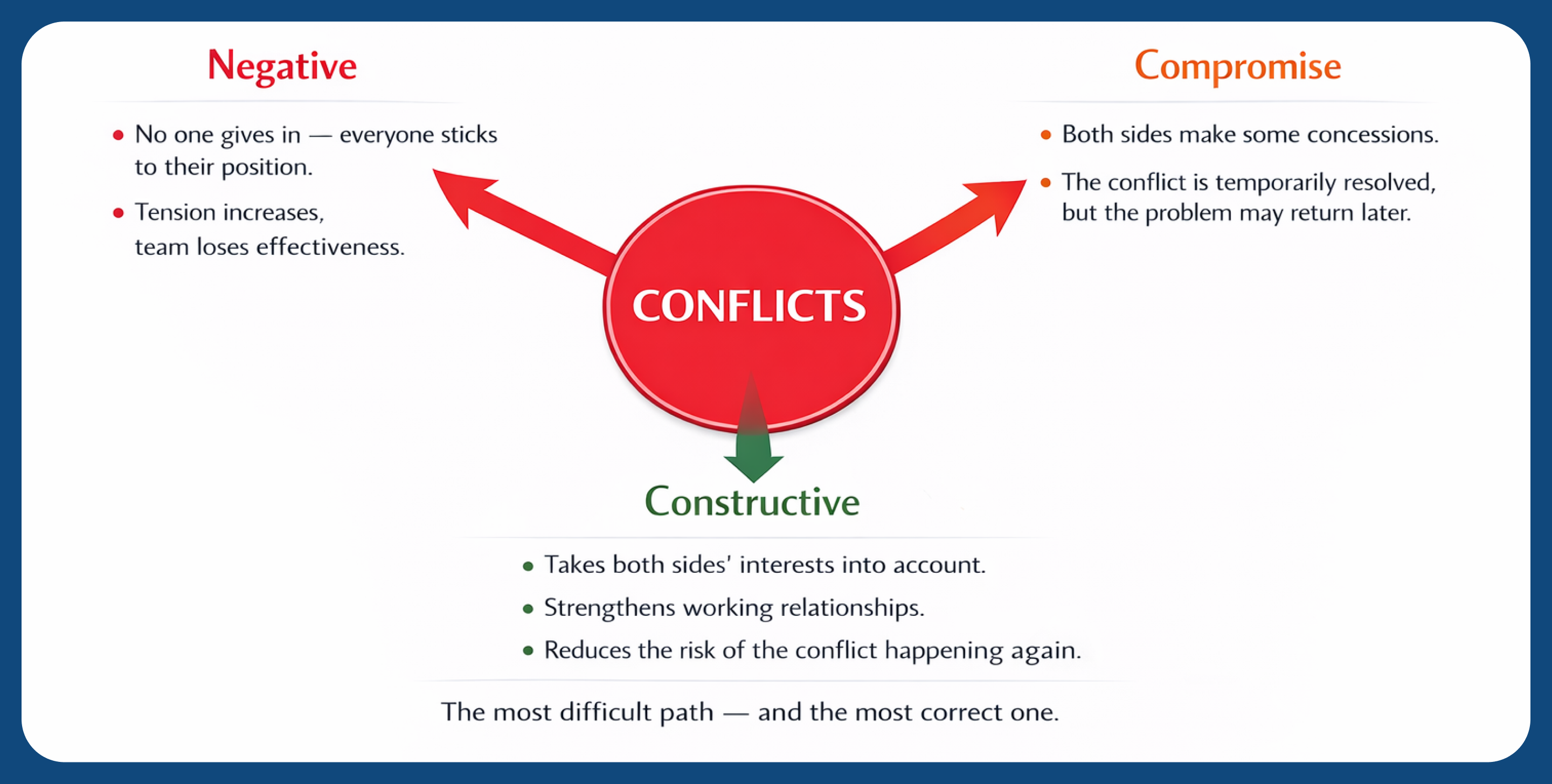

In my team management practice, I rely on three basic types of conflicts:

My name is Semyon Evelkin. I'm a backend developer and team leader who regularly deals with these situations in my work with product teams. Next is a practical analysis of how to deal with conflicts: typical scenarios and steps to resolve them.

Arguments in a team arise even where strong and motivated people work. Most often the reasons are as follows:

Many arguments begin with minor issues, but over time, these issues accumulate and escalate.

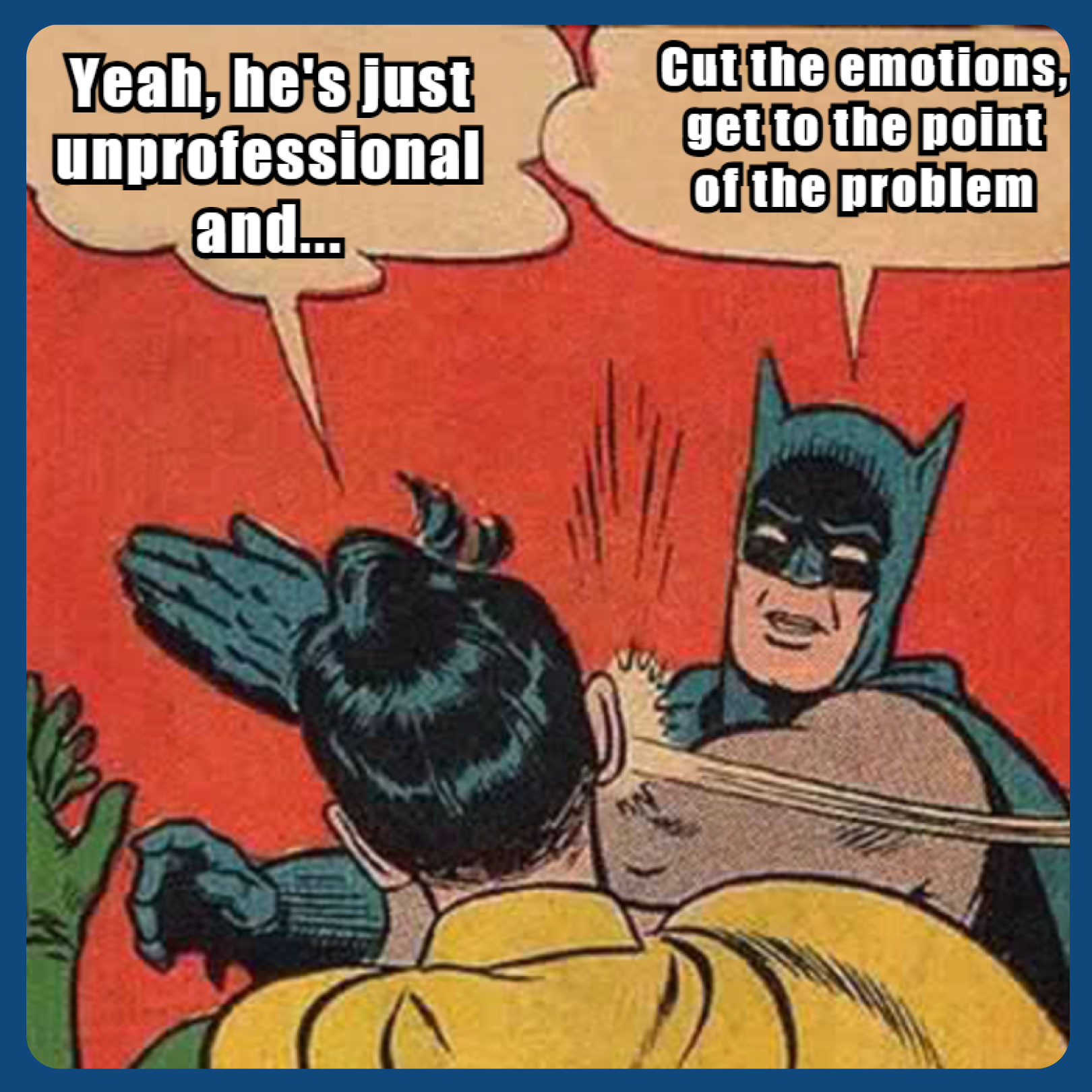

Bring conflict into an open and calm discussion to resolve it. During discussions, focus on facts, project goals, and real limitations, not emotions and personal assessments.

Managing conflict effectively means finding solutions, not blame. Compromise may be temporary, but it's better to find solutions that suit both sides and strengthen teamwork.

Common goals, clear work rules, and regular communication resolve arguments and prevent them. The problem can be resolved without drastic steps if the parties are ready for dialogue.

Conflict involves emotions and goes beyond the usual rules of communication. It can be devastating or useful if a solution is found correctly.

A typical situation: an employee regularly gets into arguments with others, but the root of the problem here is distrust of processes, management decisions, and a sense of injustice.

|

Conflict resolution |

Personal experience |

|

Individual one-on-one meeting |

I'm holding a personal meeting to discuss specifics: what doesn't suit, when, and why. This helps us find the root of the problem. |

|

Separation of responsibilities and frameworks |

I would like to specify which processes, tools, or agreements we can review and which decisions are off-limits. |

|

Involvement in improvements (if the criticism is constructive) |

I suggest that the employee get involved in finalizing the process himself or suggest a solution. This will show initiative and responsibility. |

|

Openly pronouncing the rules of interaction |

I record the team's general arrangements, including how we discuss issues and what we consider acceptable. |

|

Searching a temporary compromise |

We'll come back to the issue later, when we've had time to cool off. |

Practical examples:

1. The developer regularly has conflicts over tasks in Jira. He initiates discussions and complains about the vague descriptions. At a meeting, it turns out that due to unstructured requirements, he spends extra time and often goes into the wrong implementation. We refine the task template and conduct a short workshop on readiness criteria to reduce future conflicts.

2. The engineer criticizes the system's architecture, pointing out network operation risks. During the discussion, some are confirmed. We adjust the design and appoint an engineer for RFC-based technical support of the changes.

Typical situation: Team leader not involved. Developers and QA/designers argue over code and accuse each other of «breaking» features.

The manager's key task is to move the conflict from the emotional to the rational plane, using facts, quality criteria, and agreements instead of personal assessments and resentments.

|

Conflict resolution |

Personal experience |

|

Conduct 1:1 conversations to gather facts, examples, and implications for the work. |

I ask separately each participant in the conflict to provide specific situations and explain how they affect the timing, quality, or stability. |

|

A joint meeting |

At the meeting, I set the goals: product quality, timing, and stability. We discuss verifiable facts and criteria, not personal claims. |

|

Fixing agreements |

We record responsibilities, decision-making processes, and how to act in controversy. I make a short written summary to reduce risk of disputes and discrepancies. |

Practical examples:

1. Dispute about development approach. Team discusses architectural or technical solution. Arguments end, personalities emerge. I stop discussion and turn it into a measurable plane. We fix comparison criteria (performance, applicability in current architecture, complexity of support) and agree to make short POC. Results are compared by agreed metrics, and decision is made based on facts.

2. QA and developer tensions are rising. The developer claims QA is «too picky» and that there are «too many bugs». Arguments in tasks and chat rooms are leading to tension. During a joint meeting, we record separate logs of what we consider a bug, a change in requirements, or a misunderstanding. We improve the format of bug reports, including playback steps, expected results, and acceptance criteria. This reduces disputes and speeds up verification.

Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is part of the approach. It helps reduce conflict by focusing on facts, feelings, needs, and specific requests.

In a work environment, NVCs are a good way to have a clear conversation, especially when tension is building and a normal discussion turns into an argument.

The four steps of NVC in application form are:

Observation is to describe what happened based on facts, without assessments and interpretations.

(«It took more than three business days for two code review tasks last week.»)

Feelings are to identify your condition without blaming the other party.

(«Because of this, I feel tense because the deadlines are starting to float.»)

Needs — to relate a situation to a work need or value.

(«It's important to me that the team can predict deadlines and clearly understand priorities.»)

A request should be specific and feasible, not a requirement.

(«Can we agree that the code review for tasks with priority High is completed in a maximum of one business day?»).

This format makes the conversation less offensive and reduces defensive reactions, allowing the team to discuss the problem rationally.

Situation: conflict as a team leader/supervisor. For example, strong disagreement with a decision, harsh feedback, or emotions at a meeting.

In such cases, it's important not to defend a position at all costs, but to manage the situation to maintain trust and a working relationship.

I stop the discussion if emotions are running high. I note the question is important, but it's impossible to make a qualitative decision in that emotional state. We agree to return to the topic later.

At a separate meeting, the conversation is based on facts:

I admit to mistakes that affect people or processes. We discuss how to fix the situation and change processes to prevent recurrence.

Practical examples:

1. Negative feedback on the review. I criticized the developer's decision, and he took it personally, stopping to offer ideas. We agreed that the feedback form was incorrect, and I will provide more structured and substantive criticism.

2. I made the timing decision without consulting a key engineer. He was overwhelmed and expressed dissatisfaction at the meeting. We discussed the mistake in planning, reassembled the workload, and agreed that such decisions are made with key specialists.

I want to note that it's important to sort out conflicts that have already arisen and reduce the likelihood of future ones.

Regular one-on-one meetings are at the heart of prevention. They help identify tension, discontent, or overload early on, before it escalates into open conflict.

Team arrangements are the second important element. These are formal working rules. They include how to give feedback, how to discuss problems, when to escalate risks, and how to make decisions. Clear rules reduce misunderstandings and subjective interpretations.

The third tool is retrospectives. I use them to discuss what went wrong, focusing on processes and interactions rather than personalities. This helps the team improve their work without accumulating hidden stress.

The team leader conducts a «safe retrospective» anonymous Google Form with the questions «What's annoying? What can be improved?» if the team avoids discussion. Then there is a mandatory 30-minute conference call on the top 3 issues, with a focus on processes rather than personalities. This translates ignoring into action without coercion.